Boundary current

Boundary currents are ocean currents with dynamics determined by the presence of a coastline, and fall into two distinct categories: western boundary currents and eastern boundary currents.

Contents |

Eastern boundary currents

Eastern boundary currents are relatively shallow, broad and slow-flowing. They are found on the eastern side of oceanic basins (adjacent to the western coasts of continents). Subtropical eastern boundary currents flow equatorward, transporting cold water from higher latitudes to lower latitudes; examples include the Benguela Current, the Canary Current, the Peru Current, and the California Current. Coastal upwelling often brings nutrient-rich water into eastern boundary current regions, making them productive areas of the ocean.

Western boundary currents

Western boundary currents are warm, deep, narrow, and fast flowing currents that form on the west side of ocean basins due to western intensification. They carry warm water from the tropics poleward. Examples include the Gulf Stream, the Agulhas Current, and the Kuroshio.

Western intensification

Western intensification is the intensification of the western arm of an oceanic current, particularly a large gyre in an ocean basin. The trade winds blow westward in the tropics, and the westerlies blow eastward at mid-latitudes. This wind pattern applies a stress to the subtropical ocean surface with negative curl in the northern hemisphere and a positive curl in the southern hemisphere. The resulting Sverdrup transport is equatorward in both cases. Because of conservation of mass and potential vorticity conservation, that transport is balanced by a narrow, intense poleward current, which flows along the western boundary of the ocean basin, allowing the vorticity introduced by coastal friction to balance the vorticity input of the wind. Western intensification also occurs in the polar gyres, where the sign of the wind stress curl and the direction of the resulting currents are reversed. It is because of western intensification that the currents on the western boundary of a basin (such as the Gulf Stream, a current on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean) are stronger than those on the eastern boundary (such as the California Current, on the eastern side of the Pacific Ocean). Western intensification was first explained by the American oceanographer Henry Stommel.

In 1948, Henry Stommel published a paper in the Transactions of the American Geophysical Union Journal titled The West- ward Intensification of Wind-Driven Ocean Currents, in which he used a simple, homogeneous, rectangular ocean model to examine the streamlines and surface height contours for an ocean at a non-rotating frame, an ocean characterized by a constant Coriolis parameter and finally, a real-case ocean basin with a latitudinally-varying Coriolis parameter. In this simple, modeling setting, the principal factors that were accounted for influencing the oceanic circulation were surface wind stress, bottom friction, a variable surface height leading to horizontal pressure gradients and finally, the Coriolis effect.

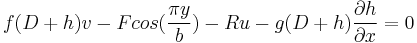

In his simplified model, he assumed an ocean of constant density and constant depth D (when at rest), varying at increments of depth h in the presence of ocean currents; he also introduced a linearized, frictional term to account for the dissipative effects that prevent the real ocean from accelerating. Starting, thus, from the steady-state momentum and continuity equations:

(1)

(1)

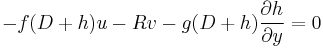

(2)

(2)

![\frac{\partial [(D%2Bh)u]}{\partial x}%2B\frac{\partial [(D%2Bh)v]}{\partial y}=0](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/16d2869bc21f85fff6ee8a3d2e5f8cc5.png) (3)

(3)

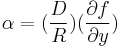

,multiplying (1) with  and (2) with

and (2) with  and using (3), he obtained the following equation (4), whose solutions for different ocean systems emphasize the role of the variation of the Coriolis parameter with latitude in inciting the strengthening of western boundary currents. Such currents are observed to be much faster, deeper, narrower and warmer than their eastern counterparts.

and using (3), he obtained the following equation (4), whose solutions for different ocean systems emphasize the role of the variation of the Coriolis parameter with latitude in inciting the strengthening of western boundary currents. Such currents are observed to be much faster, deeper, narrower and warmer than their eastern counterparts.

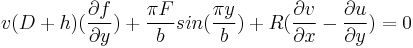

Equation (4) :

(4)

(4)

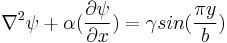

yields equation 5 :

(5)

(5)

via the use of a stremfunction ψ and when making the approximation D>>h and using the definitions:  and

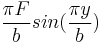

and  . F is a constant used to represent wind stress via a simple functional form:

. F is a constant used to represent wind stress via a simple functional form: [1]

[1]

One can obtain different solutions to the above equation, for different states of the modeled ocean; for a non-rotating state (zero Coriolis parameter) as well as an ocean state at which the Coriolis parameter is a constant, the ocean circulation does not demonstrate any preference toward intensification/acceleration near the western boundary. The streamlines exhibit a symmetric behavior in all directions, with the height contours demonstrating a nearly parallel relation to the streamlines, in the case of the homogeneously rotating ocean. Finally, for the case of interest -the one in which the Coriolis force is latitudinally variant - a distinct tendency for an asymmetrical streamline diagram is noted, with an observed, intense clustering toward the western part of the modeled ocean. A nice set of figures depicting the distribution of streamlines and height contours for the cases of a uniformly-rotating ocean and an ocean where the Coriolis force is linearly dependent on latitude can be found at Henry Stommel's 1948 paper on The West-ward Intensification of Wind-Driven Ocean Currents. [2]

Sverdrup Balance and Physics of Western Intensification

The physics of western intensification can be understood through a mechanism that helps maintain the vortex balance along an ocean gyre. Harald Sverdrup was the first one, preceding Henry Stommel, to attempt to explain the mid-ocean vorticity balance by looking at the relationship between surface wind forcings and the mass transport within the upper ocean layer. He assumed a geostrophic interior flow, while neglecting any frictional or viscosity effects and presuming that the circulation vanishes at some depth in the ocean. This prohibited the application of his theory to the western boundary currents, since some form of dissipative effect (bottom Ekman layer) would be later shown to be necessary to predict a closed circulation for an entire ocean basin and to counteract the wind-driven flow.

Sverdrup introduced a potential vorticity argument to connect the net, interior flow of the oceans to the surface wind stress and the incited planetary vorticity perturbations. For instance, Ekman convergence in the sub-tropics (related to the existence of the trade winds in the tropics and the westerlies in the mid-latitudes) was suggested to lead to a downward vertical velocity and therefore, a squashing of the water columns, which subsequently forces the ocean gyre to spin more slowly (via angular momentum conservation). This is accomplished via a decrease in planetary vorticity (since relative vorticity variations are not significant in large ocean circulations), a phenomenon attainable through an equator-wardly directed, interior flow that characterizes the subtropical gyre. [3] The opposite is applicable when Ekman divergence is induced, leading to Ekman absorption (suction) and a subsequent, water column stretching and poleward return flow, a characteristic of sub-polar gyres.

This return flow, as shown by Henry Stommel,[4] occurs in a meridional current, concentrated near the western boundary of an ocean basin. To balance the vorticity source induced by the wind stress forcing, Stommel introduced a linear frictional term in the Sverdrup equation, functioning as the vorticity sink. This bottom ocean, frictional drag on the horizontal flow allowed Stommel to theoretically predict a closed, basin-wide circulation, while demonstrating the west-ward intensification of wind-driven gyres and its attribution to the Coriolis variation with latitude (beta effect). Walter Munk (1950) further implemented Stommel's theory of western intensification by using a more realistic frictional term, while emphasizing "the lateral dissipation of eddy energy."[5] In this way, not only did he reproduce Stommel's results, recreating thus the circulation of a western boundary current of an ocean gyre resembling the Gulf stream, but he also showed that sup-polar gyres should develop northward of the subtropical ones, spinning in the opposite direction.

External links

- http://biophysics.sbg.ac.at/atmo/el-scans/el-nino1.jpg

- http://www.learner.org/jnorth/images/graphics/n-r/OceanCurrentsUSNOO.gif

- http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/ocng_textbook/chapter11/chapter11_02.htm

- http://www.aos.princeton.edu/WWWPUBLIC/gkv/history/Stommel48.pdf

See also

- Sverdrup Balance

- Ekman Transport

- Ocean Gyres

References

- Thurman, Harold V., Trujillo, Alan P. Introductory Oceanography Tenth Edition. ISBN 0-13-143888-3

- AMS glossary: amsglossary.allenpres.com

- Professor Raphael Kudela, UCSC, lectures OCEA1 Fall 2007

- H. Stommel, The Westward Intensification of Wind-Driven Ocean Currents, Transactions American Geophysical Union: Vol. 29, 1948

- Munk, W. H., On the wind-driven ocean circulation, J. Meteorol., Vol. 7,1950

- R. Stewart, Chapter 11: Wind Driven Ocean Circulation, website: http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/ocng_textbook/chapter11/chapter11_02.htm

- John H. Steele et al., Ocean Currents: A Derivative of the Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences, url: http://books.google.com/books?id=FYSCUH235E8C&lpg=PA522&ots=1Q4bEDlwak&dq=explain%20stommel's%20western%20intensification%20theory&pg=PA522#v=onepage&q=explain%20stommel's%20western%20intensification%20theory&f=false

- Harald Sverdrup, Wind-Driven Currents in a Baroclinic Ocean; with Application to the Equatorial Currents of the Eastern Pacific, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 33, 1947, url: http://www.jstor.org/stable/87657

Footnotes

- ^ H. Stommel, The Westward Intensification of Wind-Driven Ocean Currents, Transactions American Geophysical Union: Vol. 29, 1948

- ^ H. Stommel, The Westward Intensification of Wind-Driven Ocean Currents, Transactions: American Geophysical Union, Vol. 29, 1948

- ^ Lynne D Talley et al., Descriptive Physical Oceanography,http://books.google.com/booksid=Chb14jomm08C&pg=PA211&lpg=PA211&dq=physics+of+western+intensification+of+boundary+currents&source=bl&ots=fyeHQ-nlyf&sig=xPsXMtobl6wqaaqHHgePvpmn0QA&hl=en&ei=RljhTr-xK8XX0QHWnd3BBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAjgK#v=onepage&q=physics%20of%20western%20intensification%20of%20boundary%20currents&f=false

- ^ H. Stommel, The Westward Intensification of Wind-Driven Ocean Currents, Transactions American Geophysical Union: Vol. 29 (1948)

- ^ Wolfgang H. Berger & Elizabeth Noble ShorOcean: reflections on a century of exploration http://books.google.com/books?id=nMUqEdOd3NEC&pg=PA161&lpg=PA161&dq=walter+munk,+western+intensification&source=bl&ots=nJYxzM7rHV&sig=taR6dK-RUqtGPiDx2wzFmbD0hwk&hl=en&ei=rxvkToT3BMHr0gGPxY2oBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CB0Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=walter%20munk%2C%20western%20intensification&f=false

|

||||||||||||||||